Use balanced scorecards to follow through on business strategy

Balanced scorecards are deceptively powerful tools for defining and tracking key metrics and objectives.

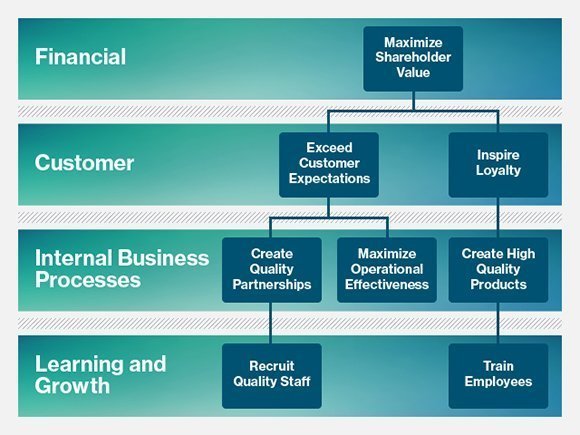

In a recent article on this site, I explained the concept of strategy maps and how they can be effective in creating a business strategy and monitoring performance. Strategy maps show how an organization’s learning and growth initiatives impact the internal business processes that serve customers and determine financial results.

Balanced scorecards, another concept developed by Robert Kaplan and David Norton of Harvard University, are the mechanism you use to fill in the details of the objectives that the organization has determined are essential to each of the four levels of the strategy map.

In the sample strategy map from the previous article, "Create High Quality Products" was listed as an internal business process.

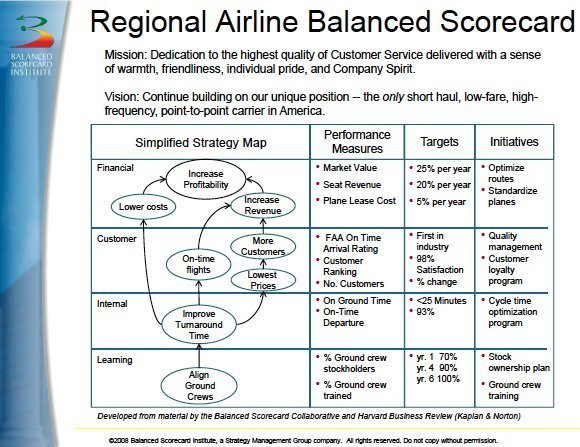

But what is the objective for creating high quality and what is the target? These are the kinds of questions an organization attempts to answer and enter into a balanced scorecard template like the one in Figure 1, from the Balance Scorecard Institute, a consultancy based in Cary, North Carolina.

For example, the internal business processes scorecard for "Create High Quality Products" might have the following elements:

Objective: Improve the quality of all manufactured products.

Measure: The number of products returned due to manufacturing defects

Target: For the one-year warranty period, fewer than three returns per 1,000 products shipped

Initiatives: Hire three new high-quality engineers. Implement a new supplier relationship management program.

Objectives, measures, targets and initiatives can be set at any level of the organization, starting with the individual. For example, a programmer in IT might want to increase his effectiveness in delivering subsystems. The measure could be the number of subsystems delivered, with a target of three in a given year. Initiatives would define each subsystem by title.

This would lead naturally to a set of initiatives by the head of programming, and then, in turn by the CIO.

The balanced scorecard defines the terms of engagement. Poor performance becomes visible, as does superior performance.

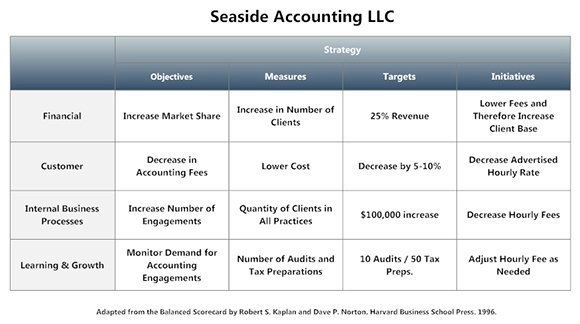

Take a look at the example in Figure 2, which comes from Kaplan and Norton’s book about balanced scorecards. There is a full set of definitions for each of the four major areas of balanced scorecards and strategy. Even though this example is relatively simple, care must be exercised.

Consider the information under Financial. The objective, "Increase Market Share," is a noble one. However, in balanced scorecards, objectives do not specify measures or targets, but overall concepts that are subject to interpretation. For example, one might think that this objective is all about revenue, but the stated measure is actually "Increase in Number of Clients." Market share in this case refers to the share of clients, not the share of revenue.

Furthermore, the target listed for this objective is 25% revenue, which somewhat contradicts the measure of the number of clients. So, is the market share goal about percentage of revenue or percentage of clients? You can have a large number of very small clients and only a modest increase in revenue.

The bottom line is to exercise care in how the components are put together.

Aligning strategy maps and balanced scorecards

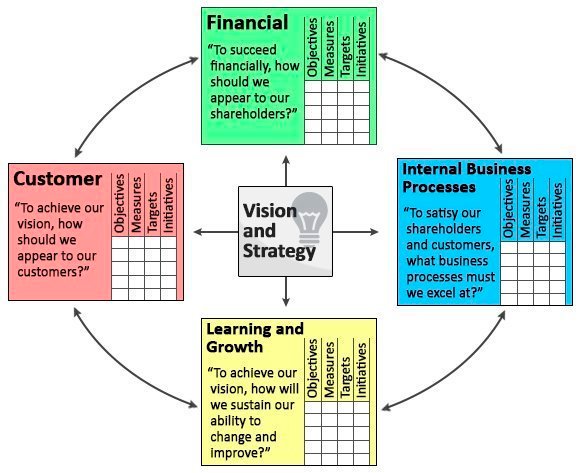

Figure 3 is an example of a balanced scorecard and strategy map that line up well. It represents a powerful combination for showing strategy hierarchically, with significant detail around each objective.

Analyzing the diagram a bit further suggests certain implications of the regional airline’s strategies and balanced scorecard objectives, along with their relationship to each other:

- Reducing the number of planes and optimizing routes are complex projects that might require project management software to execute effectively. Moreover, there is a need to understand risks and contingencies.

- Multiple strategies may be under consideration, and not all of them can be done at the same time. A working committee must analyze when and if certain strategies can be included in the overall strategic plan.

- Certain initiatives may contradict others. For example, on its face, reducing the number of planes might lower customer satisfaction because fewer choices will be on the schedule.

Balanced scorecards provide the necessary level of detail to implement the strategies defined in strategy maps. Leaving aside their relationship to strategy maps for a moment, using balanced scorecards is just good technique. All project steps should be subject to an analysis of goals, measures, targets and initiatives.

About the author:

Barry Wilderman has more than 30 years of experience as an industry analyst, researcher and consultant at such companies as Meta Group, Lawson Software, SalesOps Analytics and McKinsey and Co. He is currently president of Wilderman Associates. Contact him at [email protected] and on Twitter @BarryWilderman.